|

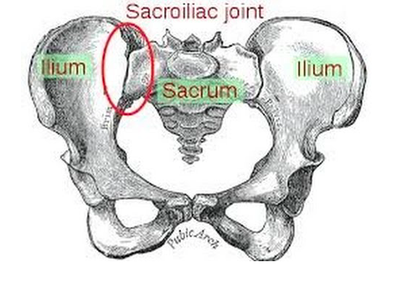

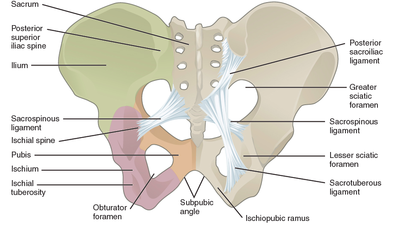

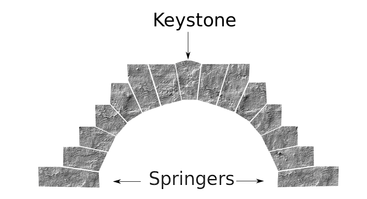

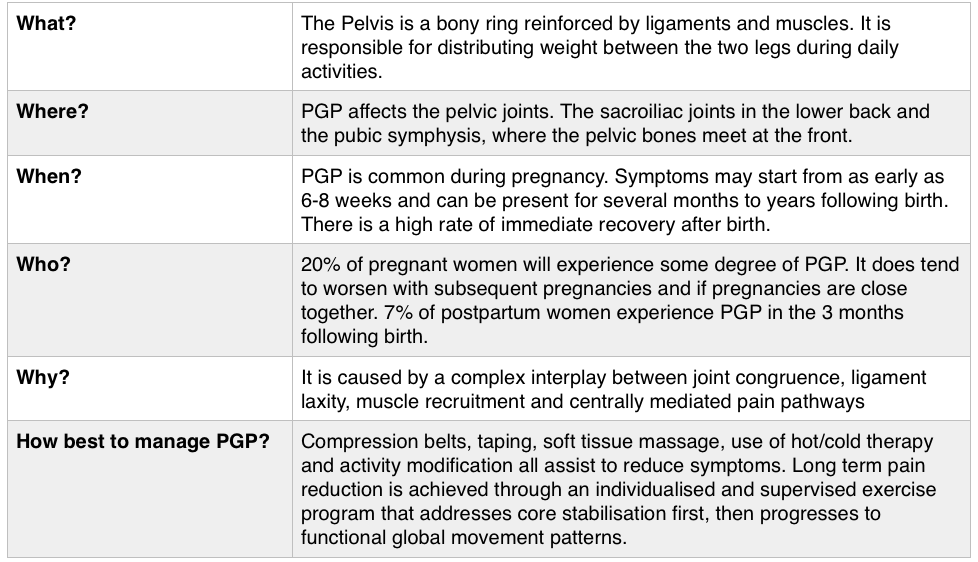

If you are suffering or have suffered with pelvic girdle pain (PGP) you know the painful ache that permeates one side of your lower back when your walking or getting dressed, or the sharp grabbing pain at the pubic bone, that pulls you up short when you take that first step from the couch. It can come and go, it can swap sides, it will ruin your sleep, and it can prevent you from being that active, happy pregnant lady you always thought you’d be. Read on to answer all your questions about PGP and how best to manage it. (Note: If it gets too heavy, you can skip to the summary cheat sheet at the end ;)) What? The pelvis is a bony ring made up of the sacrum and the ilia bones meeting at the cartilaginous pubic symphysis at the front of the body. The bony structure is reinforced by active and passive structures, (muscles and ligaments/fascia), that contribute to its stability. The role of the pelvis is to allow movement, and to transfer and absorb forces between the trunk and the limbs. In an upright position, the weight of the head, arms and trunk are transferred to the lower limbs through the sacrum, the sacro-iliac joints, the ilia bones, and into the femurs. For load to be smoothly transferred, movement at the sacroiliac joints must be minimised. The body does this in two ways: form closure and force closure. Form closure refers to the anatomical shape of the bones and the complimentary joint surfaces that cause the sacrum to form a keystone effect between the two ilia bones. During weight bearing the sacrum is forced downwards and tilts slightly forward (this is caused nutation). This causes a close-packed position of the sacroiliac joint and contributes to stability and efficient weight transfer. Force closure refers to ligaments, muscles and fascia that work across the joint to further compress and stabilise the bony surfaces. Nutation of the sacrum causes tightening of the sacroiliac ligaments. Muscles that cross the joint, (namely piriformis and gluteus maximus) will activate to provide additional stability. Additionally, studies have demonstrated that transverse abdominus, the inner-most abdominal muscle, contributes to stabilising the lower spine and the sacroiliac joints (Hodges, 1999). Where? PGP is described as pain experienced between the posterior iliac crest (top of the pelvis bone at the back) and the gluteal fold (the crease where your bottom finishes and your leg begins), predominantly at the level of the sacroiliac joints with or without referral into the back of the thigh. Pain can also be experienced in conjunction with, or exclusively in the pubic symphysis (the bone between your legs at the front). When? PGP can occur at anytime, but most commonly presents during pregnancy or postpartum. During pregnancy, the expanding and increasing weight of the uterus puts a biomechanical strain on the body, in particular the lumbar spine and the pelvis. The load on local tissues causes creep (gradual stretch), which may contribute to stimulation of mechanoreceptors inducing increased activation of pain receptors. Creep also has implications for a change in proprioception (knowing where the body is in space), and therefore motor control, which means the brain’s ability to activate and control muscle sequences for optimal movement. Additionally, the growing abdomen during pregnancy leads to a change in the angle of pull of the deep abdominals, making them less effective for stabilising the sacroiliac joint. Pregnancy comes with an increase in the hormones; relaxin, oestrogen and progesterone, which contribute to increased soft tissue laxity. The contribution toward PGP each of these hormones makes is still unclear. A systematic review of the literature in 2012, looked at the relationship between relaxin levels and pelvic girdle pain in pregnancy. Three of the four high quality studies, found no association between relaxin levels and the presence of pelvic girdle pain. In other words, despite documented high levels of hormones and increased joint laxity, this does not always correlate with the presence of PGP. Who? PGP is common during pregnancy, prevalence data from large studies show an agreed prevalence in a pregnant population of 20%. The recovery rate of PGP following pregnancy is high, with one study of 41,241 women reporting an 82.5% recovery rate in women who experienced pain during pregnancy. The overall prevalence of PGP experienced in the first three months postpartum is reported as 7%. The literature agrees that a more severe pain experience involving more than one pelvic joint during pregnancy is associated with an increased likelihood of PGP postpartum. Pregnancy and new parenthood is a time of great life-change, and brings stressors that are foreign and can seem insurmountable. Post-natal depression affects one in seven women and the ‘baby blues’ affects approximately 80% of new mothers. A lesser known condition is ante-natal depression which occurs during pregnancy and affects 10% of women (PANDA). Additionally, sleep deprivation to varying degrees impacts all new parents. Sleep deprivation has been found to cause hyperalgesic changes in the body, which contribute to chronic pain. PGP must be approached within a biopsychosocial framework. Pain is influenced by cognitive and psychosocial factors that modulate pain amplification and disability levels. It is known that ongoing pain can be centrally mediated by the forebrain, it is therefore understandable that PGP disorders can potentially be induced and /or maintained through a balance of peripheral physiological mal-adaptive behaviours, and centrally mediated pain sensitisation. Why? Putting all the who, what, where, and when together brings us to the why? So, we know the sacroiliac joint requires stability to function, that is, to transfer weight efficiently and pain-free from one leg to another. Factors that reduce this in pregnancy are increased ligament laxity, decreased efficiency of muscle activation through altered proprioception and motor control, and in the case of abdominals, less efficient angle of pull. Combine this with an increased load to transfer as the uterus expands with the growing foetus and the pelvis has it’s work cut out. However, still only one in five women will experience pelvic girdle pain. So, why? Well joint stability is not about how resistant structures are to movement or how much movement is available but instead, about the motion control that allows load to be transferred and movement to be smooth, effortless and painfree (Vleeming et al., 2008). Meaning, that it is the complex interplay between these factors that combine to present as pain. How is PGP managed? Physiotherapists have many tools that we use to reduce pelvic girdle pain, these include: -External Pelvic Compression with Belts/Tape/Compression garments -Soft Tissue Mobilisation -Hot/Cold Therapy -Activity Modification/Education -A Specific and Individualised Exercise Program. Accurate movement analysis and postural assessment is essential to long term recovery. Many studies have analysed exercise regimes; common theories are Vleeming’s anterior/oblique, posterior and vertical muscular slings. Or the functional activation pattern initially proposed by Stuge and her team in 2004 which begins with strengthening local stabilising muscles such as transverse abdominus, pelvic floor and multifidus prior to building in more global stabilisers such as latissimus dorsi, gluteus maximus, abdominal obliques and hip adductors and abductors. Results vary between studies, but there is a trend in the literature to support individualised, exercise prescription that emphasises deep stabilising muscle activation, and functional progression received one-to-one by physiotherapists over at least 6 weeks. It can be concluded that global muscles alone, despite ability to increase stability of the SIJ, have no impact and may potentially exacerbate symptoms if not recruited in an activation pattern that includes local core stabilisers of the lumbo-pelvic region as well. Supervision of exercises is important to ensure quality of exercise performance and to translate to pain reduction. Summary (the cheat sheet): Whether you have symptoms of PGP, have had symptoms, or are a health practitioner who see’s patients with PGP, I hope you got something out of this information that will help you. I practice women’s health physio in Lower Plenty, Melbourne and regularly care for women with acute and chronic PGP. I am always happy to chat and share information, so feel free to make contact with me at any time. Kym References: Albert H, Godskesen M, Westergaard J (2001) Prognosis in four syndromes of pregnancy-related pelvic pain. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 80:505–510 Heckman JD & Sassard R (1994) Musculoskeletal considerations in pregnancy. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery American Volume 76, 1720–1730. Hodges PW (1999) Is there a role for transversus abdominis in lumbo-pelvic stability? Manual Therapy 4, 74–86. Lautenbacher, S., Kundermann, B., Krieg, J. (2006). Sleep deprivation and pain perception. Sleep Medicine Reviews. 10(5): 357-369. Lillios, S., Young, J. (2012). The Effects of Core and Lower Extremity Strengtheinin on Pregnancy-Related Low Back and Pelvic Girdle Pain: A Systematic Review. Journal of Women’s Health Physical Therapy. 36(3): 116-124. Marnach, M., Ramin, K., Ramsey, P., Song, S., Stensland, J., An, K. (2003). Characterization of the relationship between joint laxity and maternal hormones in pregnancy. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 101(2): 331-335. Ostgaard, H., Zetherstrom, G., Roos-Hansson, E., Svanberg, B. (1994b). Reduction of back and posterior pelvic pain in pregnancy. Spine. 21:2777-2780. Pennick, V., Liddle, S. (2013). Interventions for preventing and treating pelvic and back pain in pregnancy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 8. Schauberger, C., Rooney, B., Goldsmith, L., Shenton, D., Silva, P., Schaper, A. (1996). Peripheral joint laxity increases in pregnancy but does not correlate with serum relaxin levels. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 174: 667-71. Stuge, B., Veered, MB., Laerum, E. et al. (2004). The efficacy of a treatment program focusing on specific stabilising exercises for pelvic girdle pain after pregnancy: a two-year follow up of a randomised clinical trial. Spine. 29:197-203. Vleeming, A., Stoeckart, R., Volkers, A., Snijders, C. (1990). Relation between form and function in the sacroiliac joint. Part 1. Clinial anatomical aspects. Spine. 15: 130-132. Vleeming, A., Volkers, A., Snijders, C., Stoeckart, C. (1990b). Relation between form and function in the sacroiliac joint. Part 2. Biomechanical aspects. Spine. 15:133-136. Vleeming et al. (2008). European Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pelvic girdle pain. Spine. 17:794-819. Vermani, E., Mittal, R., Weeks, A. (2010). Pelvic Girdle Pain and Low Back Pain in Pregnancy: A Review. Pain Practice. 10(1): 60-71. Womankind Physiotherapy is located in Eltham and Yarrambat. To make an appointment with one of our physiotherapists please call (03) 9431 2530 or book online by following the links below.

1 Comment

|

Welcome!Hi! Welcome to The Blog! Please be aware, Womankind Physiotherapy's blog is not intended to replace information and advice from your health care provider. For specific concerns regarding your health you must seek individualised care by your preferred provider.

Archives

March 2021

Categories

All

|

Women's Health Physiotherapists, Pelvic Floor Physiotherapists, Pregnancy Physiotherapists, Pre and Post Natal Physio, Pelvic Health Physio,

Pregnancy Pilates, Ultrasound for Mastitis, Breastfeeding Physio, Blocked Ducts, Pelvic Floor Exercise, Pregnancy Exercise.

Eltham. Yarrambat. Greensborough, Montmorency, Lower Plenty, Diamond Creek, Research, Rosanna, Yallambie, Watsonia.

Pregnancy Pilates, Ultrasound for Mastitis, Breastfeeding Physio, Blocked Ducts, Pelvic Floor Exercise, Pregnancy Exercise.

Eltham. Yarrambat. Greensborough, Montmorency, Lower Plenty, Diamond Creek, Research, Rosanna, Yallambie, Watsonia.

Copyright 2016 Womankind Physiotherapy

RSS Feed

RSS Feed