|

I can’t do two things at once. Well, I can, sort of…but I’m trying to stop. You know why? It’s killing me. And I don’t just mean emotionally killing me, I mean it’s actually increasing my risk of cardiovascular disease, weight gain, osteoporosis and Alzheimer’s Disease….and that’s just the start of the list. I like being on top of things as much as the next person. I like being effective and feeling in control. So….I’ve been multitasking, or so I thought. Turns out what I thought was multitasking is actually something else coined Continuous Partial Attention (CPA) and it’s really bad for me. What’s the difference? Multitasking is literally doing two things at once, such as stirring pasta whilst having a conversation. But in order to really multitask, at least one of the tasks has to be so simple it is essentially automatic, in the above example it would be stirring the pasta. Continuous partial attention refers to doing two tasks that require cognitive attention at the same time. However, in actual fact, we are not performing the two tasks simultaneously, rather rapidly switching between the two, or three, or four, and this is where things begin to go drastically wrong… An example of CPA would be; following a recipe to make a new gluten-free, dairy-free, fructose-free dinner, whilst having two independent and unrelated conversations with a 7 year old and 4 year old, and receiving a text message… at the same time. The brain does not process these cognitive demands simultaneously, rather it’s doing a crazy aerobics workout reminiscent of a Les Mills Body Attack class and leaving you equally exhausted. This kind of shifting of concentration is driven by our desire to achieve across all levels, not to miss anything (I think the kids are calling it FOMO), and due to being chronically time-poor. Setting all the problems with these motivations aside for another blog on another day… let’s deal with the issue at hand, which is what impact is this constant CPA state having on our health? Continuous Partial Attention forces us to maintain our attention in a state of hyper-vigilance which in turn keeps our bodies’ flight-or-fight response activated. The flight-or-fight response is a natural, necessary reaction to a threatening or stressful situation that requires immediate action. It turbo charges our bodies for action and for repair, it mobilises stress hormones such as adrenalin and cortisol and increases platelet concentration and immune cells in preparation for tissue damage. It is designed to be used occasionally and for brief periods of time, such as running away from a lion. When it is chronically engaged, as in constant CPA, all these chemicals and physiological changes are being turned on, with nowhere to go. We experience this as anxiety. Image: Start running; an appropriate activation of the flight-or-fight response. This long term, over-activation of the stress response causes wear and tear on the body. Some of the symptoms are

Sooo…..who still thinks they’re being efficient when they’re multitasking? But it makes sense doesn’t it. Doesn’t it feel awful when you’ve been jittering around all day from unfinished task to unfinished task, never fully seeing or hearing the world (let alone your kids) around you? It did for me. And therefore, enter Mindfulness. But sorry, you’ll have to wait. This blog is long enough and I can’t possibly do justice to the force that is Mindfulness in less than 200 words. But I hope I’ve given you some food for thought. So don’t hold your breath for the next instalment, rather take a big belly breath and actively stop doing too many things at once, it’s really not good for you. Until next time. Kym

1 Comment

So, confession time, I occasionally can be seen loitering in the ‘self help’ section of a book store. I actually find it fascinating, I am always sucked in to the opportunities for bettering my life and filled with an exciting sense that can only be described as “turning over a new leaf”. Here is the ‘self help’ section of my personal bookcase: (Oh, I feel a bit naked now!)

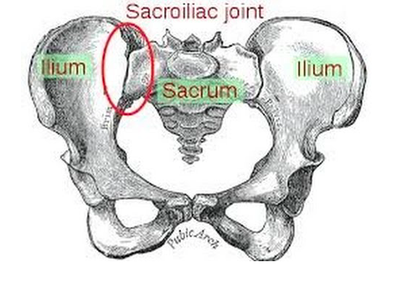

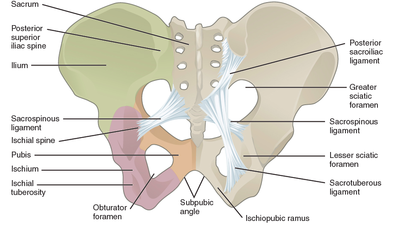

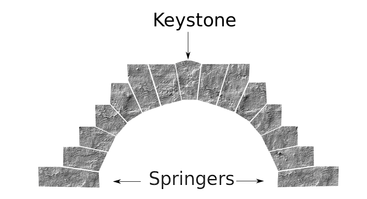

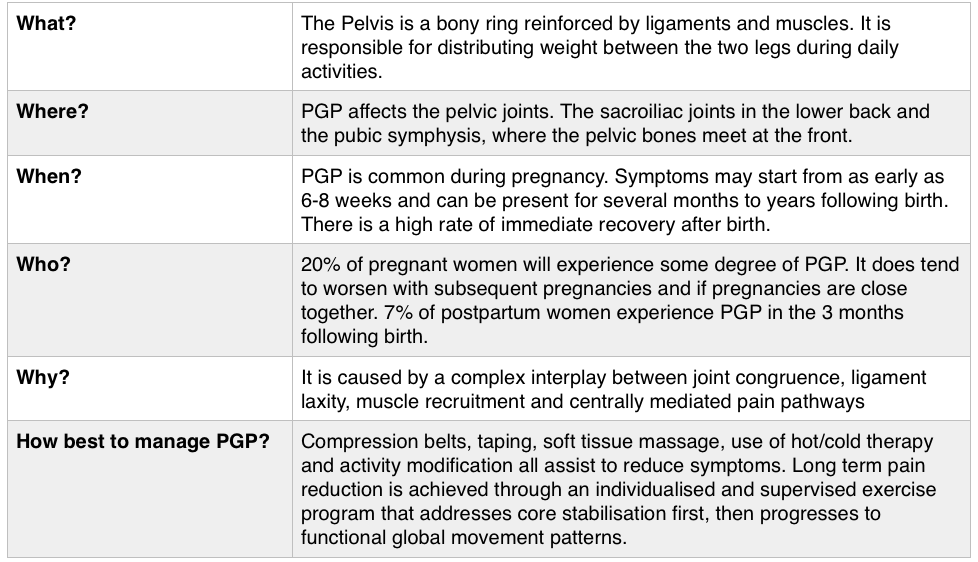

So, you may have spotted in my collection, Gary Chapman’s classic book ‘The 5 Love Languages’. For those of you who are not familiar with the 5 Love Languages, here they are listed below: -Words of Affirmation -Quality Time -Gifts -Acts of Service -Physical Touch The premise of the book is that most people identify with a particular love language and that is how they like to receive, and generally the default way that they give, love! So for example, If your love language is gifts, you like to buy people you love gifts, that is how you communicate your love. And generally, you expect gifts in return to feel loved. If your partner is speaking a different language, for example, is missing a night out with friends to be home with you watching a movie because his language is ‘Quality Time’, but you never get a look in, in his weekly shopping list, then we have a mismatch and fireworks can begin (the bad kind, not the good ones). Now I think I bought this book about 2 years into my relationship with my now husband, so no kids on the scene, not even a ring on the finger and still living separately. I distinctly remember identifying myself as a ‘Physical Touch’ linguist, I loved to feel the comfort of strong arms embracing me or the feel of his rough hands interlocked with mine as we walked down a street. My husband was a ‘Words of Affirmation’ kind of guy. This was interesting to us and fuelled a few good D&M’s (probably late at night over the cordless phones!) but I can’t recall there being much else to note. However, I do remember being very critical of the ‘Acts of Service’ language. Let me explain… Acts of Service refers to physically doing things for your partner as a way of showing you love them. For example, cleaning the house, mowing the lawn, taking out the rubbish, folding a load of washing. As a young independent woman in my early 20’s (who still lived at home and had very few responsibilities), I thought this was extremely mundane and old fashioned. How could anyone possible interpret that as passion? As an act of love? And what sort of person would you be if you expected that of someone you loved? I thought that meant you basically wanted a slave. I vowed never to speak that love language and proudly ticked the box ‘Physical Touch’ (so much more romantic!) Then, I moved out of home… And had kids…. Now; I would strip naked for a man who folds a load of my washing. Now; there is nothing sexier than my husband voluntarily cleaning up the kitchen and placing a fully cooked breakfast in front of me. Now, I get ‘Acts of Service’ as a love language. Oh boy, do I get it. And Physical Touch? Well, as a mum, I have been smothered, physically, for 7 and a half years. I have revelled in the softness of their skin, their pudgy arms clinging to my neck, their soft kisses all over my face, their little hands wrapped around my fingers. I regularly bury my face in their soft tummies to blow raspberries and they nudge their hard little heads under my chin and into my chest. I receive love through physical touch by the truckload, so I don’t actually need it from my husband. This paradigm shift in our relationship took a lot of figuring out (I’m making it sound easy here) and quite a while to get our heads around. The very rhythm of how we loved each other had to change as our needs changed. And between work, study, breastmilk, nappies, houses, kids and sleep deprivation it was hard to see things so clearly. But we got there, and lucky for me, now on a weekend morning…I get both my favourite love languages, hugs in bed with the kids while my husband cleans the kitchen and cooks breakfast! Now, you’re speaking my language! Kym. For resources and help with shifting your relationship after you have kids, check out this website: www.partnerstoparents.org If you are suffering or have suffered with pelvic girdle pain (PGP) you know the painful ache that permeates one side of your lower back when your walking or getting dressed, or the sharp grabbing pain at the pubic bone, that pulls you up short when you take that first step from the couch. It can come and go, it can swap sides, it will ruin your sleep, and it can prevent you from being that active, happy pregnant lady you always thought you’d be. Read on to answer all your questions about PGP and how best to manage it. (Note: If it gets too heavy, you can skip to the summary cheat sheet at the end ;)) What? The pelvis is a bony ring made up of the sacrum and the ilia bones meeting at the cartilaginous pubic symphysis at the front of the body. The bony structure is reinforced by active and passive structures, (muscles and ligaments/fascia), that contribute to its stability. The role of the pelvis is to allow movement, and to transfer and absorb forces between the trunk and the limbs. In an upright position, the weight of the head, arms and trunk are transferred to the lower limbs through the sacrum, the sacro-iliac joints, the ilia bones, and into the femurs. For load to be smoothly transferred, movement at the sacroiliac joints must be minimised. The body does this in two ways: form closure and force closure. Form closure refers to the anatomical shape of the bones and the complimentary joint surfaces that cause the sacrum to form a keystone effect between the two ilia bones. During weight bearing the sacrum is forced downwards and tilts slightly forward (this is caused nutation). This causes a close-packed position of the sacroiliac joint and contributes to stability and efficient weight transfer. Force closure refers to ligaments, muscles and fascia that work across the joint to further compress and stabilise the bony surfaces. Nutation of the sacrum causes tightening of the sacroiliac ligaments. Muscles that cross the joint, (namely piriformis and gluteus maximus) will activate to provide additional stability. Additionally, studies have demonstrated that transverse abdominus, the inner-most abdominal muscle, contributes to stabilising the lower spine and the sacroiliac joints (Hodges, 1999). Where? PGP is described as pain experienced between the posterior iliac crest (top of the pelvis bone at the back) and the gluteal fold (the crease where your bottom finishes and your leg begins), predominantly at the level of the sacroiliac joints with or without referral into the back of the thigh. Pain can also be experienced in conjunction with, or exclusively in the pubic symphysis (the bone between your legs at the front). When? PGP can occur at anytime, but most commonly presents during pregnancy or postpartum. During pregnancy, the expanding and increasing weight of the uterus puts a biomechanical strain on the body, in particular the lumbar spine and the pelvis. The load on local tissues causes creep (gradual stretch), which may contribute to stimulation of mechanoreceptors inducing increased activation of pain receptors. Creep also has implications for a change in proprioception (knowing where the body is in space), and therefore motor control, which means the brain’s ability to activate and control muscle sequences for optimal movement. Additionally, the growing abdomen during pregnancy leads to a change in the angle of pull of the deep abdominals, making them less effective for stabilising the sacroiliac joint. Pregnancy comes with an increase in the hormones; relaxin, oestrogen and progesterone, which contribute to increased soft tissue laxity. The contribution toward PGP each of these hormones makes is still unclear. A systematic review of the literature in 2012, looked at the relationship between relaxin levels and pelvic girdle pain in pregnancy. Three of the four high quality studies, found no association between relaxin levels and the presence of pelvic girdle pain. In other words, despite documented high levels of hormones and increased joint laxity, this does not always correlate with the presence of PGP. Who? PGP is common during pregnancy, prevalence data from large studies show an agreed prevalence in a pregnant population of 20%. The recovery rate of PGP following pregnancy is high, with one study of 41,241 women reporting an 82.5% recovery rate in women who experienced pain during pregnancy. The overall prevalence of PGP experienced in the first three months postpartum is reported as 7%. The literature agrees that a more severe pain experience involving more than one pelvic joint during pregnancy is associated with an increased likelihood of PGP postpartum. Pregnancy and new parenthood is a time of great life-change, and brings stressors that are foreign and can seem insurmountable. Post-natal depression affects one in seven women and the ‘baby blues’ affects approximately 80% of new mothers. A lesser known condition is ante-natal depression which occurs during pregnancy and affects 10% of women (PANDA). Additionally, sleep deprivation to varying degrees impacts all new parents. Sleep deprivation has been found to cause hyperalgesic changes in the body, which contribute to chronic pain. PGP must be approached within a biopsychosocial framework. Pain is influenced by cognitive and psychosocial factors that modulate pain amplification and disability levels. It is known that ongoing pain can be centrally mediated by the forebrain, it is therefore understandable that PGP disorders can potentially be induced and /or maintained through a balance of peripheral physiological mal-adaptive behaviours, and centrally mediated pain sensitisation. Why? Putting all the who, what, where, and when together brings us to the why? So, we know the sacroiliac joint requires stability to function, that is, to transfer weight efficiently and pain-free from one leg to another. Factors that reduce this in pregnancy are increased ligament laxity, decreased efficiency of muscle activation through altered proprioception and motor control, and in the case of abdominals, less efficient angle of pull. Combine this with an increased load to transfer as the uterus expands with the growing foetus and the pelvis has it’s work cut out. However, still only one in five women will experience pelvic girdle pain. So, why? Well joint stability is not about how resistant structures are to movement or how much movement is available but instead, about the motion control that allows load to be transferred and movement to be smooth, effortless and painfree (Vleeming et al., 2008). Meaning, that it is the complex interplay between these factors that combine to present as pain. How is PGP managed? Physiotherapists have many tools that we use to reduce pelvic girdle pain, these include: -External Pelvic Compression with Belts/Tape/Compression garments -Soft Tissue Mobilisation -Hot/Cold Therapy -Activity Modification/Education -A Specific and Individualised Exercise Program. Accurate movement analysis and postural assessment is essential to long term recovery. Many studies have analysed exercise regimes; common theories are Vleeming’s anterior/oblique, posterior and vertical muscular slings. Or the functional activation pattern initially proposed by Stuge and her team in 2004 which begins with strengthening local stabilising muscles such as transverse abdominus, pelvic floor and multifidus prior to building in more global stabilisers such as latissimus dorsi, gluteus maximus, abdominal obliques and hip adductors and abductors. Results vary between studies, but there is a trend in the literature to support individualised, exercise prescription that emphasises deep stabilising muscle activation, and functional progression received one-to-one by physiotherapists over at least 6 weeks. It can be concluded that global muscles alone, despite ability to increase stability of the SIJ, have no impact and may potentially exacerbate symptoms if not recruited in an activation pattern that includes local core stabilisers of the lumbo-pelvic region as well. Supervision of exercises is important to ensure quality of exercise performance and to translate to pain reduction. Summary (the cheat sheet): Whether you have symptoms of PGP, have had symptoms, or are a health practitioner who see’s patients with PGP, I hope you got something out of this information that will help you. I practice women’s health physio in Lower Plenty, Melbourne and regularly care for women with acute and chronic PGP. I am always happy to chat and share information, so feel free to make contact with me at any time. Kym References: Albert H, Godskesen M, Westergaard J (2001) Prognosis in four syndromes of pregnancy-related pelvic pain. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 80:505–510 Heckman JD & Sassard R (1994) Musculoskeletal considerations in pregnancy. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery American Volume 76, 1720–1730. Hodges PW (1999) Is there a role for transversus abdominis in lumbo-pelvic stability? Manual Therapy 4, 74–86. Lautenbacher, S., Kundermann, B., Krieg, J. (2006). Sleep deprivation and pain perception. Sleep Medicine Reviews. 10(5): 357-369. Lillios, S., Young, J. (2012). The Effects of Core and Lower Extremity Strengtheinin on Pregnancy-Related Low Back and Pelvic Girdle Pain: A Systematic Review. Journal of Women’s Health Physical Therapy. 36(3): 116-124. Marnach, M., Ramin, K., Ramsey, P., Song, S., Stensland, J., An, K. (2003). Characterization of the relationship between joint laxity and maternal hormones in pregnancy. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 101(2): 331-335. Ostgaard, H., Zetherstrom, G., Roos-Hansson, E., Svanberg, B. (1994b). Reduction of back and posterior pelvic pain in pregnancy. Spine. 21:2777-2780. Pennick, V., Liddle, S. (2013). Interventions for preventing and treating pelvic and back pain in pregnancy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 8. Schauberger, C., Rooney, B., Goldsmith, L., Shenton, D., Silva, P., Schaper, A. (1996). Peripheral joint laxity increases in pregnancy but does not correlate with serum relaxin levels. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 174: 667-71. Stuge, B., Veered, MB., Laerum, E. et al. (2004). The efficacy of a treatment program focusing on specific stabilising exercises for pelvic girdle pain after pregnancy: a two-year follow up of a randomised clinical trial. Spine. 29:197-203. Vleeming, A., Stoeckart, R., Volkers, A., Snijders, C. (1990). Relation between form and function in the sacroiliac joint. Part 1. Clinial anatomical aspects. Spine. 15: 130-132. Vleeming, A., Volkers, A., Snijders, C., Stoeckart, C. (1990b). Relation between form and function in the sacroiliac joint. Part 2. Biomechanical aspects. Spine. 15:133-136. Vleeming et al. (2008). European Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pelvic girdle pain. Spine. 17:794-819. Vermani, E., Mittal, R., Weeks, A. (2010). Pelvic Girdle Pain and Low Back Pain in Pregnancy: A Review. Pain Practice. 10(1): 60-71. |

Welcome!Hi! Welcome to The Blog! Please be aware, Womankind Physiotherapy's blog is not intended to replace information and advice from your health care provider. For specific concerns regarding your health you must seek individualised care by your preferred provider.

Archives

March 2021

Categories

All

|

Women's Health Physiotherapists, Pelvic Floor Physiotherapists, Pregnancy Physiotherapists, Pre and Post Natal Physio, Pelvic Health Physio,

Pregnancy Pilates, Ultrasound for Mastitis, Breastfeeding Physio, Blocked Ducts, Pelvic Floor Exercise, Pregnancy Exercise.

Eltham. Yarrambat. Greensborough, Montmorency, Lower Plenty, Diamond Creek, Research, Rosanna, Yallambie, Watsonia.

Pregnancy Pilates, Ultrasound for Mastitis, Breastfeeding Physio, Blocked Ducts, Pelvic Floor Exercise, Pregnancy Exercise.

Eltham. Yarrambat. Greensborough, Montmorency, Lower Plenty, Diamond Creek, Research, Rosanna, Yallambie, Watsonia.

Copyright 2016 Womankind Physiotherapy

RSS Feed

RSS Feed